By Allyson Nadia Field

In January 2017, I received an email from Dino Everett, the film archivist at the University of Southern California, with an image from an unidentified 50ft nitrate print from c.1900. Dino was struck by what appeared to be “a legitimate early positive depiction of well dressed black people from the silent era.” In his email, he asked a simple question—“does this seem important?”

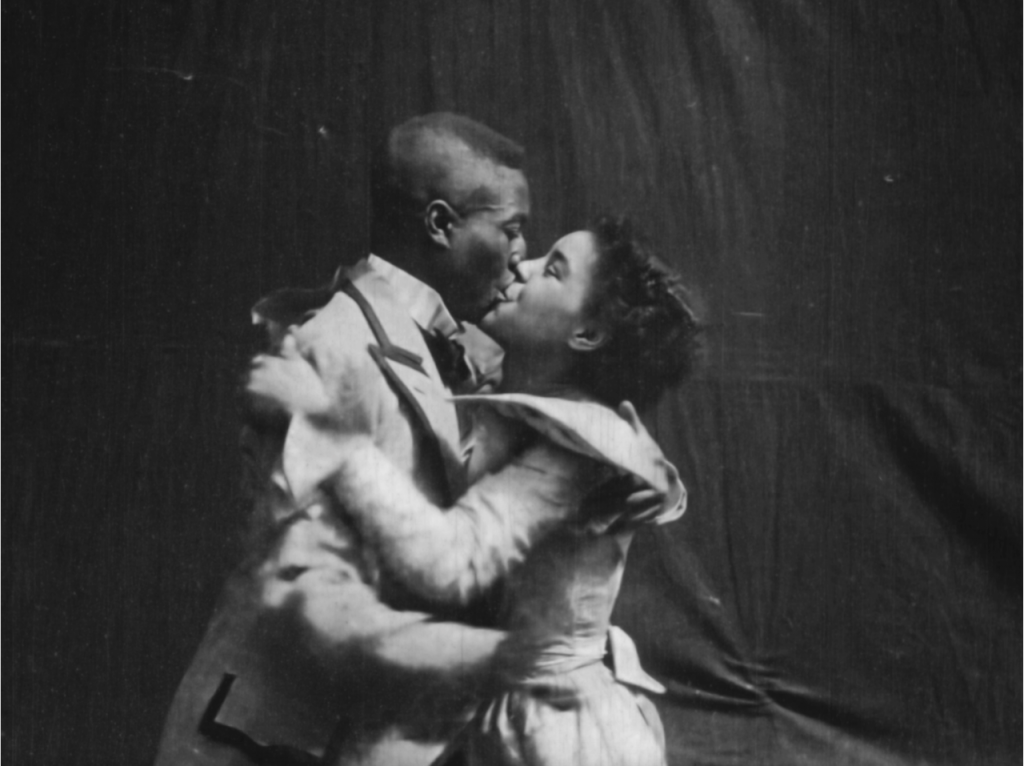

The answer was pretty clearly “yes.” What struck me as so self-evidently extraordinary was the fact that the man and woman embrace repeatedly and in a strikingly non-caricatured manner. Unlike the prevalent depiction of African Americans in early cinema, which portrayed them in demeaning, racist caricatures, these performers are not the butt of any joke, nor is their kiss a punch line. Their performance is naturalistic, and they express joy and intimacy in a presentation of seemingly genuine affection.

Investigating both material evidence and surviving print records, Dino and I worked together to identify the film as Something Good-Negro Kiss, made by William Selig in 1898 in Chicago. With the help of archivists at the Museum of Modern Art, we were also able to identify the performers as Chicago-based minstrel and vaudeville actors Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown, two of the famed “Rag-Time Four” who performed in the Midwest at this time and popularized a “cake dance” version of the cakewalk.

Short as it is, Something Good-Negro Kiss prompts a quite radical rethinking of racialized representation and performance in early cinema. This is not just because it adds to our knowledge of the period—though, given that over 90% of early American films are considered lost, new material is not trivial. It is also a rare positive and naturalistic representation of Black humanity at a time of deeply antipathetic racist representations

Yet what makes the film so important is the way it quickly leads into deeper waters. Something Good-Negro Kiss was sold to exhibitors as a “burlesque” and parody of Edison’s famed John C. Rice-May Irwin Kiss (1896). This was a selling point—and the film was one of a number of such burlesques—but this allusion to Edison’s film in Selig’s advertising led me to rethink my understanding of more canonical early films and their cultural context. Although her career is now largely forgotten, May Irwin was in fact a famous minstrel performer at the time, known for popularizing “coon songs” in which she, fascinatingly, adopted the persona of a threatening Black man. Indeed, while we know that the moment Edison’s film captures is the notorious kissing scene from the stage play “The Widow Jones,” it’s not part of historians’ discussion of that film that the play in fact featured a number of Irwin’s “coon songs.” Seen in this light, Something Good-Negro Kiss can be understood as making visible what was only implicit in the Edison film, restoring racialized performativity to the screen and, importantly, refuting the racist caricature that May Irwin’s presence carries.

This context, only briefly indicated here, teaches an important lesson. Film history has tended to posit sophisticated debates about race and performance as concerns of the late 20th and 21st century, but here we see just how prevalent and complex these imbrications were for early cinema as well. In my current work on the emergence of American cinema in the late 19th century, I hope to restore legibility to these films by reassessing the interrelations of forms of minstrelsy, vaudeville, and cinema at a period of complexly functioning racial tropes and significations. My larger project, then, reconsiders the history of early American cinema in light of archival rediscoveries like Something Good-Negro Kiss and with a fuller understanding of minstrelsy’s influence on early filmmaking, screen performance, and cinema audiences.

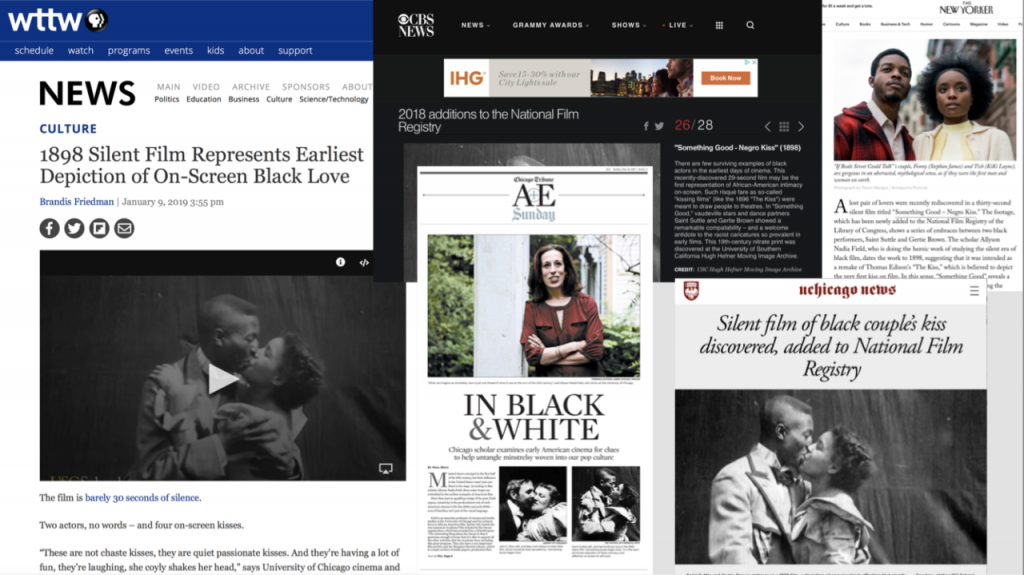

As important as the film is to historians, others have seized on this rediscovery. Dino and I have been interviewed on radio and television, and for a range of print and online newspapers and magazines. We have also shared our research with scholars and archivists at the Orphan Film Symposium, the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, and in scholarly talks and presentations (including at Domitor in Rochester in 2018). This attention has resulted in additional rediscoveries. Several archivists and private collectors have contacted us with material that informs our understanding not only of Something Good-Negro Kiss but of race in early cinema more generally. Much of the work to come will involve parsing this material: we will be able to access a fuller history of the careers of Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown (and other performers of the time), to assess the significance of the cakewalk on stage and screen in this period, and even to speculate on the possible implications of the screening of this passionate kiss between African Americans for a range of audiences across the country in different exhibition contexts.

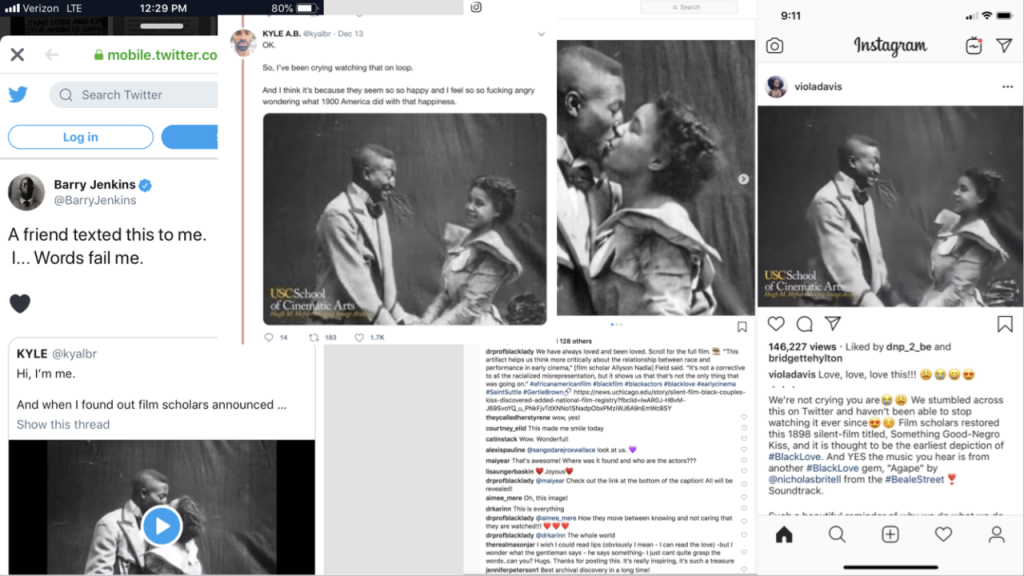

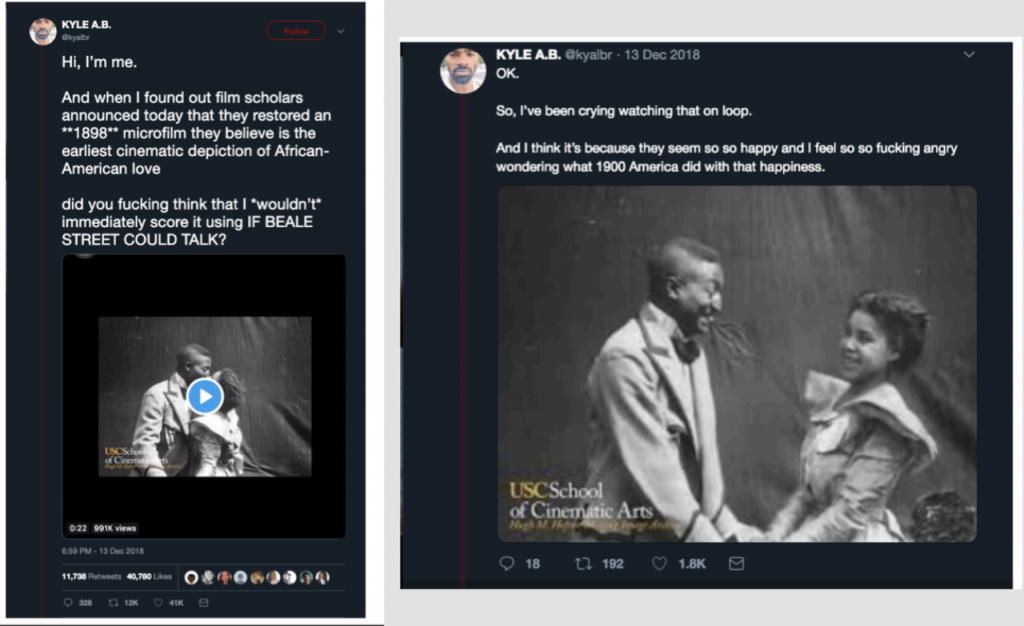

In addition to being an exciting archival rediscovery, Something Good-Negro Kiss clearly has resonance for the contemporary moment, as an interest in it has reached beyond the community of scholars and archivists. As a rare artifact of Black love, Something Good-Negro Kiss resonates deeply with questions of race and representation in contemporary Hollywood. This became evident after I nominated Something Good-Negro Kiss to the National Film Registry, to which it was officially added in December 2018. Netflix counsel and Twitter personality, Kyle Alex Brett, set the film to the score of Barry Jenkins’s If Beale Street Could Talk,and The Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN) series Black Love Doc posted it to Instagram with sobbing emojis: “We’re not crying you are!” The resulting exposure from these initial posts created a tremendous response through social media with shares and comments from significant Hollywood figures like Jenkins, Viola Davis, Tracee Ellis Ross, Lena Waithe, Jada Pinkett Smith, Mj Rodriguez, Tambay Obenson, and Janelle Monae. Poet and president of the Mellon Foundation Elizabeth Alexander shared it; the creator of #Oscars SoWhite, April Reign, retweeted it; and “The Black List” founder Franklin Leonard commented, “Absolutely broke me.”

While surprising, especially for those of us working in the relative bubble of archives and academia, the response makes sense. The film resonates today with contemporary representation of Black love on screen, in films such as Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk—a connection made all the more apparent by Kyle Alex Brett’s initial tweet. Social media comments have accordingly focused on the performers’ unreserved and untempered expression of joy.

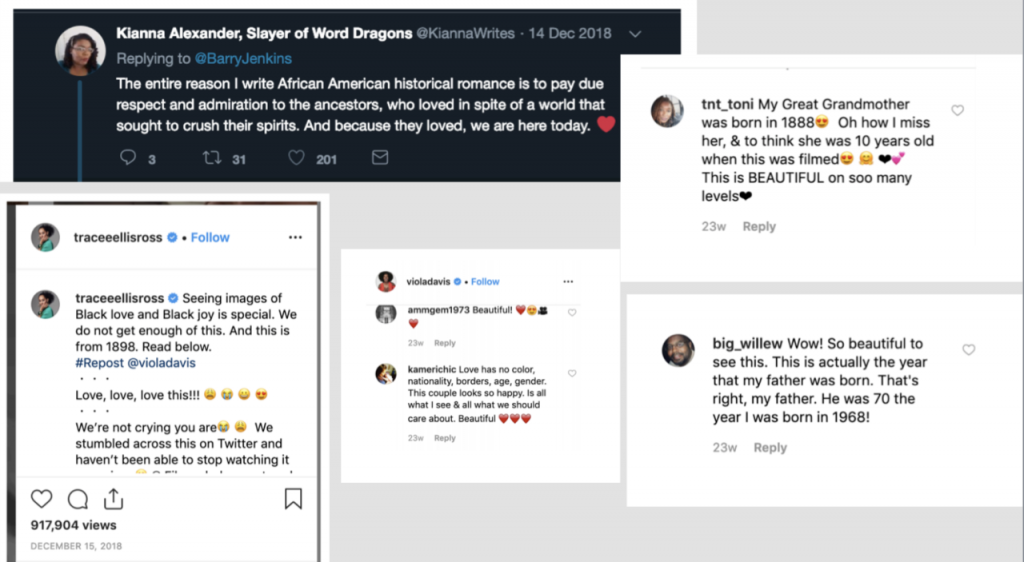

But social media comments have also reflected a bittersweet response. “There is something so sweet yet so sad about this footage,” one viewer wrote, while Kyle Alex Brett himself said, “I’ve been crying watching that on loop. And I think it’s because they seem so happy and I feel so angry wondering what 1900 did with that happiness.” Along with moving stories of parents and grandparents falling in love, there were a number of comments that pointed to the historical erasure and misrepresentation of African American love and affection in American cinema and that celebrated the power that cinema has to assert such a powerful image against the systematic refutation of Black humanity—“Imagine if our grandparents and parents were able to see this in their prime!”—“This is like opening a time capsule and seeing love in its purest form. It’s beautiful to see, but hard to know the hateful times they were living in.” As Tracee Ellis Ross noted, “Seeing images of Black love and Black joy is special. We do not get enough of this. And this is from 1898.”

At a time of virulent systemic and representational racism (a statement true in 1898 as it is now), representation matters. As Goddess of Gumbo told her Twitter followers: “artists were fighting the battle of representation… no blackface, just #BlackLove.” That these responses, and these questions, still persist is a major impetus for pursuing this scholarship. And it is a reminder of the imperative that film scholarship has to witness the incredible resilience of African American performers fighting for self-representation and for a screen image rooted not in caricature but in humanity.

The extensive response the film elicited is also a reminder of the broad impact that archivist-scholar collaborations can have. As Domitor members, we know this; but it’s nonetheless rewarding to witness the impact that Dino Everett’s rediscovery of the nitrate print of Something Good-Negro Kiss can have on contemporary audiences. For those of us who study early cinema, archivists are our lifeline, so it matters when someone with the platform of writer and Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King tells his 2 million Facebook followers, “Archivists are truly superheroes.”