To sleep, perchance to dream – ay, there’s the rub, for a succession of trans- and intercontinental flights make for a poor sleeping pattern at the Giornate. For many of us it must be inevitable to spend at least a few days in a state between waking and sleeping, or sleeping and sleepwalking, and heightened silent movie going provokes this experience even when you’ve finally gotten over your circadian dysrhythmia, otherwise known as the lag contracted from your jet. Do you sometimes feel (or look) like Cesare from Das Cabinet des dr. Caligari? Then this blog is for you.

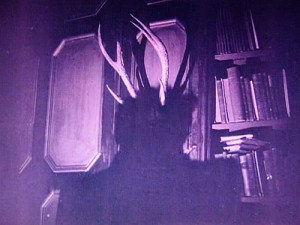

Yesterday’s hallucinatory offering Schatten: Eine nächtliche Halluzination (Arthur Robison, 1923) played happily into the Giornate experience, as it featured a magical enchanter of shadows (Alexander Granach) that forced his audience to go to sleep and experience vivid dreams – I doubt that any film we have seen so far could be a better metaphor. Of course, the film raises many other interesting questions as well; Schatten asks, for instance, “can one be cuckolded by a shadow?” The answer is a resounding “yes.” Why the master of the house felt the need to bring so many spine-chilling speci-men with tight breeches into his house is another question. To say that Schatten leaves little to the imagination would be a lie, but those pants are an entirely different matter.

The costumes are as much a part of the fantasy that Schatten serves up as its rich framing devices, from ornamental doorways to convoluted mirror shots. The aesthetics of the film affirm the world of the dream, though Schatten makes the diegetic “real” world a little harder to distinguish from the diegetic dream world than most other films dealing with the world of dreams. In Maurice Tourneur’s The Poor Little Rich Girl (1917), for instance, the title’s namesake Gwendolyn (Mary Pickford) enters the overly aestheticized world of dreams when her servants drug her and she tumbles down the steps of her house. The transition to this world of shadows is announced by a camera matte arch (proscenium or pictorial) that appears while the background fades into scenographical volumes of steps, arches, and windows, reminiscent of the popular stage design work of Edward Gordon Craig and Adolphe Appia. Tourneur’s adaptation of Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird (1918) also goes in for the separation of the two worlds through matted arches and stylization à la New Stagecraft designers, though the difference between the two worlds is about as slim as in Schatten.

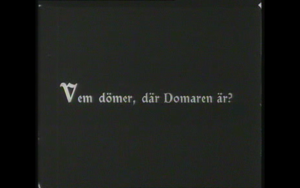

The difference between the real world and that of dreams can be hard to gauge. In Schatten, after all, the real world sees a magical shadow master ride off into an arched abyss of darkness; granted, if you have been coming to Pordenone long enough, you might have seen similar porking around – we apologize, Prosciutteria Dok. Sleep is induced willingly and unwillingly at the Giornate, for whether you go to a screening in the morning, the afternoon, or the evening, someone will always be snoring loudly. You might have noticed your own head bobbing away frantically at times, and you might have even let out an involuntary yelp after awaking from a split-second nap. The point is that we’ve all been there. We should acknowledge that nodding off influences your viewing experience in an interesting way, creating visual memories that are fragmented and might cone to overlap with those from other films or even with real life moments. Have you never regaled someone with an anecdote that you later realized was all made up from motion pictures? I’m just saying, who judges?

I should be remiss here not to quote my close friend and former “mentee” at the Pordenone Collegium, Kris Woods, who wrote an excellent Collegium piece on the experience of sleeping at Pordenone in 2010 – I am counting on my fellow media archaeologists to dig it up in its entirety. Kris is currently part of the programming (wolf)gang at Wolf Kino in Berlin, and incidentally “Wolf wants cinema to be a dream machine that creates unforgettable memories and encounters – real and fictional.”

Kris thematized his moments of falling asleep during screenings and tried hard to cope with the associated guilt:

“the notion that sleep was a reaction to films not entirely of my liking was categorically dismissed; as can the climate for, despite it being slightly warmer than my hometown, it in no way caused me to swelter and snooze uncontrollably. Could it then be the programme itself? Could it be a result of a festival in which for twelve hours a day for seven days films are screened continuously with the occasional break for the necessary intake of food and water? Films that, due to the rarity of opportunity to view them on a large screen with live accompaniment, and in most cases to view at all, drive a desire to see as much as possible for fear that I will never see them again. Did I simply overexert myself in my desire to watch everything?

(…)

I feel that somehow, by watching so many films in such a short period, to the point where they, due partly to the problem of sleep mentioned above, begin to blend into one, I am somehow being unappreciative of them. My act of obsessive watching disassociates the films from their historical and cultural contexts.”

In some ways, these words can be seen as a call for moderation; to temper one’s self lest the festival experience becomes a Hiroshi Sugimoto photograph in your mind, or, in the worst case scenario, you will develop Andy Warhol syndrome and have your head filled with the images of all the hairy men you have seen sleeping during the Giornate. Should you be inspired, don’t forget to check out Mireille Berton and Silvio Alovisio’s call for papers, Cinema, dream and hallucination from the origins to the early twenties (1895-1925)