If our last post was all about staying “woke” (come on, millennials, read this blog), then this is an encouragement to dream a little more. Every year at the Giornate, long lost films pop up, unearthed from a New Zealand hayloft, a Pordenone warehouse, a dusty Czech archive, or even the Yukon dirt. Not just any films either, films by Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles, films starring Louise Brooks, and, this Wednesday, even films by the Lumière company. It happens so often that the Giornate has a category for it, “Rediscoveries,” and that a number of us feel it is only a matter of time before the 42-reel version of Erich von Stroheim’s Greed (1924) rears its head – but when that happens, will we really want to see an eight-hour film about a dentist?

We shouldn’t take these rediscoveries for granted, whether they happen on a regular basis or not, for every presumably lost film that turns up is like a treasure chest waiting to be opened. Actually, if we want to get that right for film: imagine the treasure chest not as an ornate gem carved out of a single palm tree trunk by the finest of woodworking pirates, but rather as a cardboard box that has been slowly eaten away by dust and mold from resting in a cellar for 70 years; in between the reflective polyester running gear from the 1970s and the dolphin-shaped trinkets from that dolphin phase your grandparents went through in the early 1990s are a few rusty cans that smell vaguely like vinegar and, when opened, reveal a roll of film that has completely clotted together.

The thrill of the chase is less about breaking open a marble floor tile labeled “X” in a Venetian library and more like continuously weeding through people’s homemade 8mm collections – what those poor archivists must have seen – in the hopes of finding something good. To be fair, many of us here do still hope that dressing like the early cinema equivalent of Indiana Jones will magically bring about the same treasure-finding capacities. Needless to say, the discovery of no less than twenty Lumière films in their original containers and on 35mm is absolutely remarkable. The films are estimated to range from between 1896 and 1903 and were acquired by the George Eastman Museum. The films were preserved and restored by Samuel B. Lane, a student of the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation at the George Eastman Museum and the recipient of the 2017 Haghefilm Fellowship; this means that Lane was invited to restore the films alongside the pros at the Haghefilm Digitaal film lab in Amsterdam.

One of the benefits of coming to Le Giornate? Everyone in attendance was seeing the films projected on the silver screen in 35mm for the first time – Eastman staff included – and many of these Lumière films have not even been identified yet. To put it in Indiana Jones terms, it’s the same as opening the Ark of the Covenant: you don’t know what will happen, so you have to look – or wait, was that the other way around? At any rate, the effect is the same.

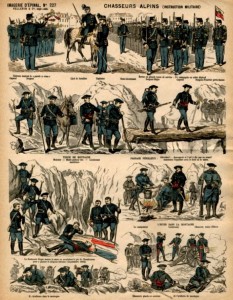

As if playing into the metaphor of the “thrill of the hunt,” the first set of face-melting frames presented us with “hunters,” more specifically the Chasseurs Alpins (Alpine Hunters), or the elite mountain infantry of the French army, jumping over obstacles in pairs. Interesting fact, the mountain corps was created in the late-nineteenth century to keep the Italians from invading France through the Alps, and here we are presenting the films for the first time in the North of Italy. The synchronization of their jumps and the way they were taught to brace for impact by bending at the knees is certainly comical, but at the same time the rhythm of their routine is oddly hypnotizing.

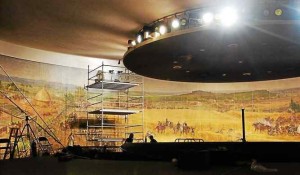

More highlights of the presentation included soldiers dancing with one another as if their lives depended on it; a jousting contest at a medieval fair; a cameo by the famed Parisian chocolaterie, Chocolat Menier, on the side of a train (possibly from their factory in Noisiel, which constructed a railroad line there in 1881); and, last but certainly not least, a highly unique visualization of a “pre-cinema” medium, a cyclorama (a panorama on the inside of a cylindrical platform).

A number of Lumière films were clearly part of little series on a particular subject, and piecing back together the history behind these films by the company that lent its name to the cinema will be an even more fascinating journey. I should point out here that a fragmented history is often part and parcel of the film restoration process; restorations are often rediscoveries in another form: archives discover they have complementary reels of films that haven’t been seen in their original form since the period in which they were first released. These “rediscoveries” are no less miraculous, as was obvious, for instance, in the case of Der Gang in die Nacht (Love’s Mockery; 1920), the earliest surviving F.W. Murnau film that was screened on Thursday, right after the newly pieced together Der Golem (Paul Wegener and Heinrich Galeen, 1915). Der Gang is hypnotizing in its own right, featuring intense stylized performances by a post-Homunculus Olaf Fønss and a pre-Caligari Conrad Veidt, as well as breathtaking imagery of the sky and the sea. While a certain regular remarked that everyone in the film was sleepwalking, I would say that this doesn’t do justice to this creeping, if convoluted, tale of love and regret.