By Aurore Spiers

When the announcement for the Eighteenth International Domitor Conference, “A Long Early Cinema?” was released in fall 2023, I felt immediate excitement at the prospect of “reinterrogat[ing],” as the call for papers put it, “the meanings of ‘early cinema’ today, at a time when the discipline of film history—along with archiving, festivals, and programming—is undergoing vast transformations.” The conference, which just took place at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, Austria, from June 12–15, 2024, offered its participants the wonderful opportunity to discuss whether a “long early cinema” existed, beyond the traditional periodization from the 1890s through 1915. Scholars from around the world gave inspiring presentations on a wide variety of topics, including early film’s many afterlives in historical and contemporary avant-garde cinemas, as well as feminist and postcolonial approaches to early film history. (See the full conference program here.) For me, it also presented an opportunity to reflect, in collaboration with many colleagues, on how we teach early cinema today.

2024 Domitor Conference at the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Early cinema constitutes a challenge for those of us who teach film and media history today. In the eyes of our Gen Z students, early cinema is seen as outdated, slow, uninteresting, and even sometimes offensive. At the Domitor conference, where I presented on a panel alongside Jiří Anger and Doron Galili on June 12, 2024, I asked: why even try to keep early cinema alive in our classrooms? What are the rewards of teaching early cinema today? What does early cinema tell us that we and our students need to know? My goal was not to provoke, but to explore the creative ways in which we can reactivate early cinema for our students within the context of our current digital ecologies. Drawing on published work, as well as on materials—course syllabi, assignments, slides—shared with me by colleagues through a survey, I began to think about early cinema as it is being taught at academic institutions in the United States and beyond. The survey I designed asked film and media instructors about their pedagogical approach to early cinema, from discussion topics and screening lists to lesson plans and assignments. I’m therefore indebted to the teachers who took the time, in the busy end-of-the-school-year period, to fill out the survey. In particular, I want to thank responding graduate students and other precariously employed academics, whose contributions to teaching are vitally important yet remain critically undervalued. Thanks to their collaboration, my presentation began to examine how digital technologies and practices like video sharing, social media, and digital humanities projects have informed our pedagogical engagement with early cinema.

Author’s Domitor presentation, June 12, 2024, Vienna, Austria.

Photo Credit: Enrique Moreno Ceballos.

Because our teaching is necessarily shaped by institutional access to resources, I should emphasize that my own experience has been as a graduate student and postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago, where I taught several introductory courses as well as advanced seminars to undergraduates (and some graduate/masters students) between 2017 and 2024. Since the 1990s, the University of Chicago has been a special place for the study, and, indeed, the teaching, of early cinema. Founded by Miriam Hansen, the Department of Cinema and Media Studies has benefitted from the University’s abundant financial resources, including in the form of the Film Studies Center (and its large library of DVDs, Blu-rays, and film prints) and the Logan Center for the Arts (and its state-of-the-art multi-format theater). It has also been home not only to Hansen, Tom Gunning, and Yuri Tsivian, but also to several generations of their doctoral students—Doron Galili, Mario Slugan, Jacqueline Stewart, Colin Williamson, Artemis Willis, and Joshua Yumibe, to name just a few—who have become prominent early cinema historians themselves. (Many of them are also dedicated Domitor members!)

Today, early cinema remains integral to Chicago’s curriculum. Both undergraduate and graduate students in Cinema and Media Studies are required to take “History of International Cinema I: The Silent Era,” and other core classes like “Introduction to Film” and “Film and the Moving Image” prominently feature films by the Lumière brothers, Georges Méliès, and Alice Guy Blaché, often discussed through Gunning’s “cinema of attractions” paradigm. Yet, despite early cinema’s privileged position in the curriculum, I have encountered similar challenges to those my colleagues have faced at other academic institutions. These challenges—mainly, students’ lack of prior knowledge, and, even worse, their “resistance to the topic,” as one of my survey respondents phrased it—motivated me to reach out to colleagues with the goal of together finding successful strategies for teaching early cinema today. In my classes, for instance, I have found it generative, following Caroline Golum and Don McHoull, to ask students about the similarities they see between the “cinema of attractions” and contemporary viral videos. But I craved for a broader conversation, one that would include colleagues from different academic institutions around the world.

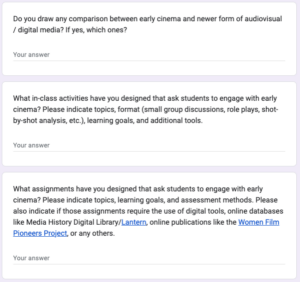

Sample questions from the author’s survey.

My survey about “Teaching Early Cinema Today,” and my Domitor presentation, which I hope will lead to a larger collaborative project, were my attempt at starting that broader conversation. As of June 12, 2024, the survey I circulated among Domitor members and other colleagues had received 18 responses (11 from tenure-track or tenured faculty, 5 from graduate students or adjunct faculty, 1 from visiting faculty, and 1 from emeritus faculty, most of whom teach in the United States). In these responses, early cinema, often understood in the broadest sense as cinema from the silent period, became reactivated as a vibrant object of innovative pedagogy, primarily in historical survey classes in departments of film and media studies. To answer the challenges previously mentioned—students’ lack of prior knowledge and “resistance to the topic”—instructors have developed strategies that I argue follow two axes: first, they examine how early cinema intersects with new media when it comes to style and aesthetics, on the one hand, and affect and experience, on the other; and, second, they explore how new media provide us with new tools for teaching early cinema today. (The survey admittedly encouraged instructors to think along these two axes, but its questions remained quite open.)

Most instructors provided answers that suggest an already deep investment in the relationship between early cinema and new media. Some consistently bring together the “cinema of attractions” and contemporary short videos from social media, especially cat and dance videos from TikTok, which demonstrate a similar kind of non-narrative aesthetic, exhibitionism, and direct address to the viewer. Others compare the emergence of cinema in the 1890s to recent moments of technological change, including, for example, the launch of new Apple products like the iPhone and the Apple Watch. Still others focus on what Maggie Hennefeld described in the survey as a “voracious appetite for playful/spontaneous/experimental mediation of everyday life” to be found both at the turn of the twentieth century and in our current digital age. All instructors also use one or several of the following digital resources: social media and related apps like SaveTok; YouTube and other streaming platforms; ChatGPT; Lantern, the Internet Archive, or ProQuest Historical Newspapers; the Women Film Pioneers Project (edited by Jane Gaines and Kate Saccone out of Columbia University Libraries); and the Audiovisual Lexicon for Media Analysis (edited by Vincent Longo and Matthew Solomon from the University of Michigan). Through the survey, I also identified three primary types of assignments that instructors have designed. These assignments belong to the following categories: Critical Analysis, which asks students to engage in close reading, thinking, and writing; Creative Making, which asks students to make or remake early films with their phones or other video technology; and Primary Research, which asks students to search for extant archival materials online.

Preliminary survey results as presented by the author at the Domitor conference.

While these results are preliminary, I hope that by sharing the survey again this summer—and by highlighting it here—I can gather more insights from colleagues teaching outside the United States. I also hope to collaborate with colleagues to make their assignments and materials available online as part of Domitor’s Teaching Resources. Yet it seems clear already that early cinema’s many challenges also come with many rewards for instructors and students alike, as a result of what Gunning calls (in a different context) “re-enchantment through aesthetic de-familiarization.” Based on my interpretation of the survey’s results so far, I would also add that early films—because of their short duration, unique aesthetics, and historical reception and exhibition—are particularly valuable for the teaching of contemporary film and media practices. In designing innovative assignments, instructors of film and media demonstrate their keen pedagogical skills by reactivating early cinema for their students. They also reveal the importance of early cinema for understanding how new digital media work, which is why assessing our pedagogical practices is so important. Keeping early cinema alive in our classrooms is necessary. It is also, as the Domitor conference showed, great fun and joy.

*******

“Teaching Resources” are already available on Domitor’s website: https://domitor.org/teaching-resources/. You may also consult “Resources for Educators” from the Media History Digital Library: https://mediahistoryproject.org/about/educators.php. If you are interested in participating in the survey, please reach out to Aurore Spiers at aspiers@tamu.edu.