By Hugo Ljungbäck

Media studies and its many sub-fields have over the past decade borne witness to an influx of thinking about matter: between “new materialism,” media forensics, infrastructure studies, and “new media” history, media scholars are increasingly turning their attention away from media texts and content toward the physical media technologies and objects themselves and their processes of mediation. As a point in case, the 2018 Domitor conference on “Provenance and Early Cinema” invited scholars to further think about the production, circulation, and preservation of early film culture through its material objects—primarily film prints—and the archives that care for them. Provenance, an approach borrowed from art history, indeed provides a useful framework to trace the origins of material artifacts and map their travel through time and space to supplement traditional textual analysis, trace alternative lineages, and address omissions and fill in gaps in film history.

But while provenance uses the material film object as a means to an end, the still-nascent discipline of media archaeology studies the artifact as an end in itself, providing a complementary lens to rethink the materiality of early cinema, film history, and matter(s) of medium-specificity, intermediality, and digitization. Media archaeology is a sort of bastard child: as a discipline—sub-field? approach? practice?—it remains a multi-pronged, methodologically rich, oft-interdisciplinary endeavor without any singular institutional home. Whether undertaken by humanists, artists, or science and technology scholars, what unifies media-archaeological projects is their roots in materiality and object-oriented inquiry: the media artifact drives the investigation, whether it be a film print, a lantern slide, an optical toy, or a digital bit.

As such, media archaeology has accommodated a wide range of perspectives and applications, many of which could advance and complement current approaches to the study of early cinema: media archaeology encompasses textual, discursive, and cultural analysis, media forensics and reverse-engineering of technological artifacts, and media-theoretical and philosophical inquiries, as well as more conceptual projects like speculative narratives about imaginary devices and other forms of artistic production. These and more were all represented at the recent Media Matter: Media-Archaeological Research and Artistic Practice conference at Stockholm University in late November 2019, which sought to rethink the relationship among media objects, materiality, history, and art practice by exploring a wide range of both well-known and forgotten media artifacts.

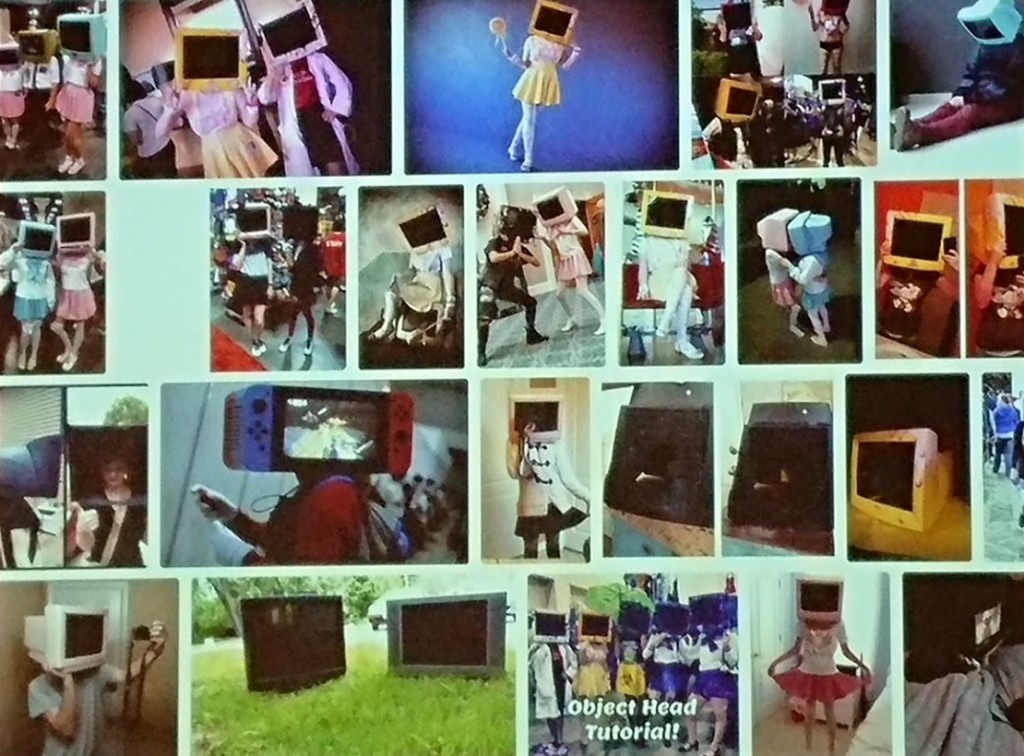

It is perhaps fitting that this international conference should bring together scholars and artists from around the globe to “neutral territory” in Stockholm, a city incidentally located between Berlin’s Humboldt University—the home of the late Friedrich Kittler’s “Medienwissenschaft” (“media science”) and Wolfgang Ernst’s Media Archaeological Fundus—and Finland’s University of Turku—the intellectual breeding ground of cultural historian Erkki Huhtamo (and oft-times Ernst and Huhtamo collaborator Jussi Parikka). Over the three-day conference, keynotes Ernst and Huhtamo generated productive—and at times intense—debate between their individual approaches to media archaeology. While Ernst advocated for thinking about media objects suspended from time and separate from context to get to the bottom of their mechanisms and functions (what he terms “archaeography”), Huhtamo advanced a more culturally-situated reading of the object at hand (in his case study, “object heads”) through “topos study,” by tracing recurring motifs and clichés and how their meanings have changed over time.

These approaches, and many in-between, were illustrated throughout the conference by papers on subjects spanning the entire twentieth century and beyond, from museum dioramas and Mexican Fotoesculturas to TV snow, internet cables, and salt. Shedding light on rare, unusual, and forgotten—if not entirely imaginary—media relics of the past, or looking at familiar objects through new tools and lenses, the conference raised questions about historiographical methods, digital humanities, artistic inquiry, and the role of media scholarship in the twenty-first century. In his opening remarks, Doron Galili suggested that part of media archaeology’s unique position at the intersection of scholarly and artistic production is its ability to engage publics beyond the academy, and accessibility was a concern that resurfaced in various ways across several papers.

A few presenters showed directly how media-archaeological inquiries could benefit the study of early cinema. Media archaeology encourages us to question not only the historical narrative of technological progress from primitive to advanced: by returning to “dead media” and obsolete technologies, we can trace alternative histories and modes of production (of nitrate stock, lens glass, or color dyes), rethink the commonly-acknowledged “firsts” of film history (from the Daguerreotype to the Kinetoscope), and reassess the importance of the many false-starts of cinema through the technologies that either didn’t quite work or were never built to begin with.

In this spirit, Ulrich Meurer kicked off the conference with a paper on artist Henry Jesionka’s speculative “Ancient Cinema” project, a fictive archaeological find of first-century Roman glass plates and a motion picture projector discovered in Zadar, Croatia, provoking us to rethink cinema’s origin myth in nineteenth-century optical toys and experiments, instead extending film history two thousand years into the past. Meanwhile, art historian Sara Callahan explored the legacy of Eadweard Muybridge’s iconic locomotion studies for artists like Bruce McLean and Keith Arnatt, who repurposed the deadpan “scientificity” of Muybridge’s serial aesthetic, or Steven Pippin, who restaged Muybridge’s trip-wired camera setup by converting twelve trip-wired washing machines into cameras for his Laundromat-Locomotion series, bringing Muybridge’s late-nineteenth-century apparatus into the present. Both Meurer and Callahan showed how artists—through myth or appropriation—help complicate the temporality of media and continue to raise questions about materiality and indexicality in the age of the digital.

Discussing their work with magic lantern slides in the KADOC Redemptorist collection, Frank Kessler and Sabine Lenk considered the issue of context loss when materials enter archives, sets of illustrated lecture slides are re-organized out of sequence, and duplicate copies are discarded, making it difficult to tell how individual slides were used and what value they held. Instead of thinking about slides as individual photographs—as strictly carriers of images, which can be re-categorized and organized ahistorically by topic, subject, or location, according to the archive’s interests—Kessler and Lenk advocated for preserving slides in their original projection context, as part of a “media constellation.” By reconstructing sets as they would have been performed and experienced by contemporaneous lecturers and audiences—in projection order, along with lecture notes—together, Kessler and Lenk argue, these sets can tell us far more about nineteenth-century screen and media culture than any individual image on its own.

Showing clips made from his DIY digitization suite, Eric Faden provided an exciting sneak-peak at rare rolls of Japanese paper films from the late 1920s, showing how Japan’s rich history of paper crafts inspired filmmakers at a moment of celluloid scarcity to explore alternative media formats, and discussing his own effort to re-photograph these delicate paper film objects to be able to view them. Finally, using Rodney Graham’s “Mini Rotary Psycho Opticon” as a starting point, Benoît Turquety provided an illustrative overview of foot pedals and cranks, from bicycles and musical instruments to pre-cinematic toys and sewing machines, exploring how the physical interaction between human and machine regulates the apparatus’ dispositif and disciplines the body of the spectator/performer.

As this cursory glance should illustrate, media-archaeological studies could provide alternative entry-points and open new areas of inquiry for early cinema scholarship. The conference’s lively and productive exchange of ideas provided a forum to raise new issues and point toward new directions in our ever-expansive field—a field that could use some extra guidance after losing one of its foremost champions and advocates in the recent passing of Thomas Elsaesser, a foundational figure for media-archaeological approaches to the study of early cinema and “new film history.” While his prolific work will continue to guide us as we enter the next decade, the generative conversations held in F-salen at the Swedish Film Institute may help set the agenda for future research, as we continue to explore (how) media matter.