How wide should you cast the research net in early cinema studies? Working on my book about the British pioneer Robert Paul has thrown up some interesting challenges, and discoveries. One of the main problems – as with most early film work – is that so much has been lost. In Paul’s case, less than one tenth of the 800-odd films he produced between 1895 and 1910 are currently known to have survived.[1]

How wide should you cast the research net in early cinema studies? Working on my book about the British pioneer Robert Paul has thrown up some interesting challenges, and discoveries. One of the main problems – as with most early film work – is that so much has been lost. In Paul’s case, less than one tenth of the 800-odd films he produced between 1895 and 1910 are currently known to have survived.[1]

But even if very few more are identified, there’s still a lot that can be done with what we have – which is where catalogues become important. Detailed catalogues were a feature of film production and distribution in the decade between about 1898 and 1908. After this, with the transition to longer ‘headliners’ under way, and new terms of business in the rental market, films would be promoted singly. But for the previous decade, even if distressingly few films survive from most producers, we still have some extraordinarily detailed, even eloquent, catalogue descriptions. In Paul’s case, the main films were often illustrated, some with multiple images covering different scenes.

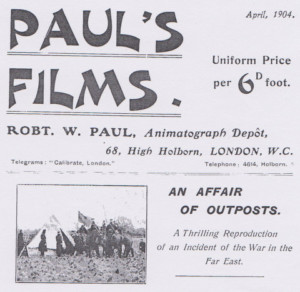

In a few cases, I feel it’s possible to make quite a detailed assessment of the film – at least its content and scope – on the basis of these palimpsests. Two by Paul that particularly fascinate me are films he made about the Russo-Japanese War in 1904: An Affair of Outposts and All For the Love of a Geisha. Given that we only have very early examples of Paul’s ‘reproductions’ of war stories, dating from the Boer War, these more developed, multi-scene dramas take us into new territory and invite speculation on many matters. Their action involves varied landscapes (where were they filmed?), and distinctive costumes for the Japanese and Russian uniforms (did Paul’s studio have a costume wardrobe?). Above all, of course, where did the stories come from?

I haven’t found any convincing way of answering such questions, but the amount of information we have about these and other films should be enough to begin to discuss their significance. Which raises the issue of context. Until I started to investigate these films, I had never really thought about the relevance of the war between Japan and Russia for Britain. It was certainly decisive for both countries involved, but why would Paul have thought it worth marking with at least two elaborate action-dramas – both of which seem distinctly pro-Japanese according to their plot synopses?

The more I researched, it became clear that Britain was linked at various levels to the rapidly industrialising Japan, and actually had a treaty connection, in the event of Japan being attacked. Back in the 1880s, two of Paul’s teachers at London’s newest technical college were British scientists and engineers who had worked in Japan, laying the groundwork for its new technological infrastructure. So he might have already been sympathetic. And British public opinion at the time of this distant war appears to have been pro-Japanese, or at least unsympathetic to Russia. And, yes, Puccini’s recent Madame Butterfly was probably making cross-cultural romance fashionable…

These speculations lead directly on to a film in Paul’s 1905 catalogue, also apparently lost, which I’d never paid much attention to before. Titled Goaded to Anarchy, it’s another drama of some substance and ambition, which traced the suppression of a plot by Russian anarchists, and the resulting revenge by one of them on a Tsarist general. The plot has quite a lot in common with narratives we know well, ranging from several of Joseph Conrad’s to Andrei Bely’s great novel Petersburg. And of course – I suddenly realised – it must have been prompted by news of the attempted revolution in Russia in 1905, one episode of which became the subject of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. We know that news of Russia’s turmoil certainly reached Western Europe, and Pathé’s enterprising reconstruction of the Potemkin mutiny in 1905, La Revolution russe, has survived.

But who knew that there was a British response in the same year as the unsuccessful revolution? And that its attitude appears to have been sympathetic to those challenging Russian autocracy? Conrad’s two great novels The Secret Agent and Under Western Eyes both came later. Meanwhile, there was a series of terrorist incidents between 1909 and 1911, culminating in the notorious ‘Siege of Sydney Street’, which brought former revolutionaries from the Russian Empire to London.

All of which may seem a far cry from researching Robert Paul, most of whose extant films are whimsical comedies, such as The Unfortunate Policeman (1905) and The ? Motorist (1906). But actually, I think we’re in danger of selling short some of the key early figures by looking only at the surviving films, and focusing mainly on their formal qualities. Sadly, early film history has been largely written on the basis of what few films have randomly survived. Indeed, this is true of most silent-era film history, and of even later periods.

I firmly believe we need to challenge this happenstance, and take account of important films that we know much about, even if we can’t see them today. And I have encouraged my students researching in the silent era to be unafraid of discussing films that no longer exist, or do so only in fragmentary form. Obviously it’s hard to make value judgements about these, but then another vice of early film history has been its partiality to value judgements based on what interests us, rather than what may have interested producers and audiences a century ago.

Reading the catalogues carefully, and trying to evoke the contexts that may have prompted their varied contents, are surely vital parts of the research process. We will never know how decisions were made in early studios such as Paul’s in North London. Or what viewers thought of their offerings, in the days before organised reviewing. But thanks to the catalogues, and the contextual search resources we have today, we can get a little closer.

Ian Christie

[1] All of Paul’s extant films were published on a DVD I curated for the British Film Institute in 2006, and many of these have since found their way onto YouTube, with Stephen Horne’s excellent accompaniment.