By Tristan Ettleman

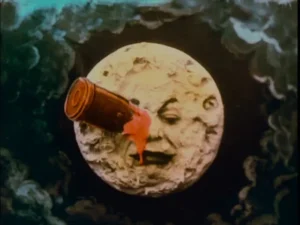

It all started with A Trip to the Moon (Georges Méliès, 1902), as it probably did for many now invested in some form or another in early cinema. Inspired by a newfound cinephilia in my later high school years, and my tendency to have to “go back to the beginning,” I sought out the earliest film I, like many others, was aware of. The iconic image of the Man in the Moon with a bullet-like ship lodged in his eye has been ingrained in the visual pop culture imagination, and the impact of that mythical image for one curious about the earliest days of cinema cannot be overstated. But I am part of a generation that had, in late adolescence, incredible access to a whole swath of media history at its fingertips, and I soon discovered that film history, of course, did not start with Méliès. Then I discovered that it’s not so easy to say it started with any one individual, or group, or work. That’s when things got exciting.

Spurred by this electrifying viewing, I started to develop extensive viewing lists for myself in 2014, and slowly but surely progressed through a rich cinematic history. Three years later, in 2017, I decided to start a critical essay series that would showcase my five favorite films of each year stretching back to cinema’s foundations. Aptly, I titled it “The 5 Best Films of Every Year Ever.” I didn’t really have any kind of large audience; this was essentially a small-scale blog project on Medium for my own edification, as the process of putting my thoughts into writing helped incentivize me to become familiar with the films and their historical context.

The homepage of The 5 Best Films of Every Year Ever podcast

As I wrote, my online presence grew, and I’ve found that many discover these essays of mine based on the whims of search engine optimization algorithms. There were discussions about others’ favorite films of any given year, and I discovered others with similar projects, full of films I had never seen or given quite the same attention. I began thinking about how a diversity of opinions could be pulled into the perhaps reductive world of “best of” lists in a media landscape that popularizes such digestible formats, from the Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time to the American Film Institute’s 100 Years…100 Movies lists. As much as I appreciate many of the classics and established beats in the story of cinema, I became interested in how this synthesis could present alternative histories or challenge established “canons.”

Of course, there is a valid argument to be made, and it has been made many times in the film community, that “best of” lists, awards shows, and the like are reductive; after all, art is not competitive. In large part I agree with that. But besides how lists help organize my own thinking, the reality is that many people would like a manageable way to engage with film history, and lists can serve as a useful and less daunting starting point to help guide the uninitiated to the treasures of our rich cinematic heritage; they do not necessarily share our obsession.

Inspired by some of my own (very modest) success in presenting lesser-known chapters of film history on TikTok, I thought about how I could move beyond representing just my particular biases and aesthetic tastes. Building off my essay series and experience teaching film, I started the podcast incarnation of The 5 Best Films of Every Year Ever in mid-2024.

“The List” page on The 5 Best Films of Every Year Ever podcast site

Each season of the show focuses on one year (with the first actually dealing with the unruly 1890s as a whole in a prologue of sorts) and features five guests across five episodes providing their five favorite/best/most representative films (however they’d like to interpret that) of that year. The 1901 season provides a great example of that creative interpretation. Domitor vice president Grazia Ingravalle very intentionally tackled the opposite of “best” films by examining the effects of colonialism through five actualities. On the other hand, Lawrence Napper got very local with an array of picks dominated by the Mitchell & Kenyon trove. And past Domitor co-president Ian Christie blended picks of the most cited films of that year, such as The Big Swallow and The Death of Poor Joe, with the casual beauty of a seemingly simple tram film from William K.L. Dickson.

For every season, short introductory and concluding episodes set up and summarize the year and conversations, making for seven episodes that explore the depth of the year. All films submitted by guests and listeners for a particular year are listed on the podcast’s website, and I also compile a list of the five titles from each year that appeared most often through these submissions. This practice has already been gratifying, with some listeners informing me they’ve put together their own viewing lists based on the wide range of picks that have been shared already in these early days of the show. The exciting sense of community and collaboration being developed through this process is strengthened not only by my own attempts to invite guests with diverse interests, but also the helpful recommendations of those guests for other invitees and films with which I’m not familiar.

Institutions like MoMA couch educational content about early cinema in the parlance of the social media platforms on which they operate. “It was a lot harder to make dance videos before TikTok,” as they suggest in reference to Annabelle Serpentine Dance (Dickson, 1895).

As an academic, I want to present the “whole context” of each film, including production methods, the people behind the scenes, and the social conditions of the period, and not just the film text itself, and I have a particular instinct for how that should be done. But in order to adapt to our social media landscape, which encourages passive media consumption and information intake over active searching, I embrace the reductive nature of recommending a manageable set of films, including by posting excerpts of the podcast on TikTok, which reaches new audiences every day. The goal of The 5 Best Films of Every Year Ever is to seek out a diverse array of voices which can provide better informed viewing recommendations than social media algorithms, which determine what users of a platform like TikTok see, can.

On the one hand, the video platform cements established trends and expectations, with clips of films like A Trip to the Moon and The Great Train Robbery (Edwin S. Porter, 1903) performing above average in both view counts and engagement (likes and comments). But on the other hand, excerpts of the podcast featuring such obscurities as Peter Elfelt’s The Execution (1903) catch viewer’s attention through the passionate arguments made for their remarkability (in this case, by Pordenone Silent Film Festival director Jay Weissberg, for the strikingly prescient cinematographic composition of the film).

I am not suggesting that these small clips are redefining TikTok’s algorithms in a significant way. But the surprising interaction of real users’ behavior with algorithmic platforms can lead to exciting passive discoveries that would have otherwise had to be actively initiated—like my own journey was over a decade ago. It’s fun to learn from other people’s likes and dislikes, isn’t it? If the podcast exposes just one person to one film that changes their life, then I’ll consider it a success.

If you would like to share a different film history through The 5 Best Films of Every Year Ever, you can contact Tristan Ettleman at trettleman@gmail.com.