By Grazia Ingravalle

It’s again that time of the year—we’ve reviewed materials from our most recent trip to the archive, organized our findings, and submitted our proposals. Submissions have rolled in and the program for the 12th edition of the Orphan Film Symposium, to be held at EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam next May, has just come out. So, it seems just about the right time to browse through one’s notes from the 2019 Symposium (June 6–7). As I review my memories now, I relive the excitement and wonder at being part of this very special edition.

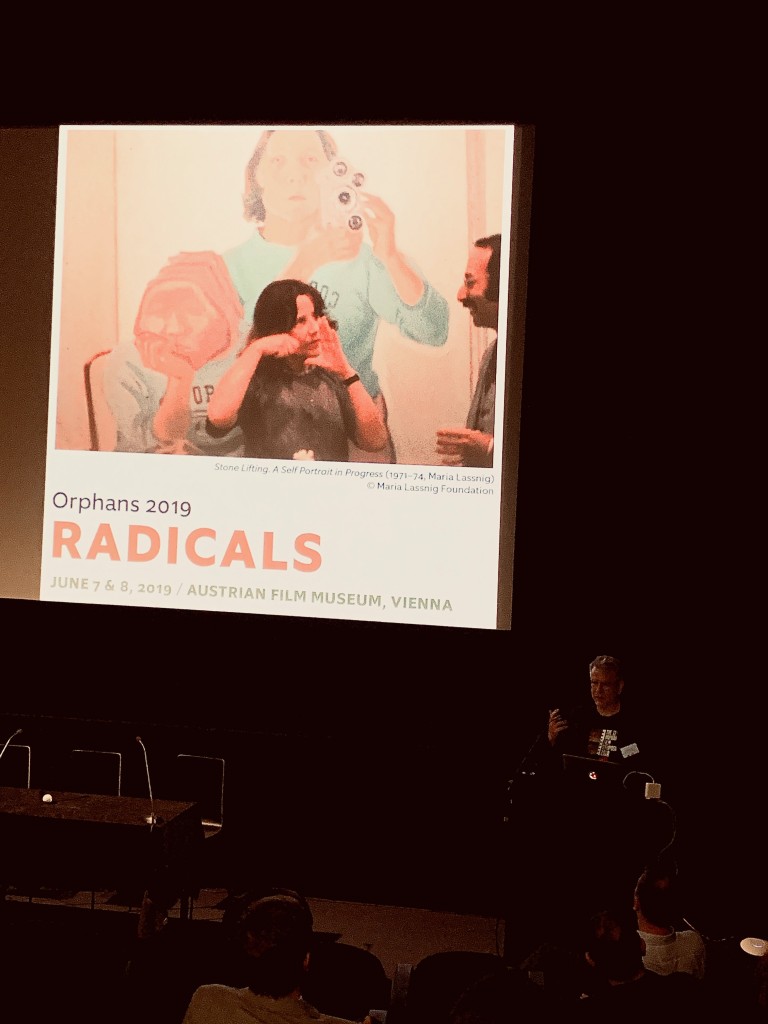

Half conference, half film program, for over twenty years, the Orphan Film Symposium has brought together a community of archivists, filmmakers, scholars, programmers, restorers, festival directors, and curators, to share their enthusiasm and knowledge about films orphaned of their authors, right claimants, or institutional caretakers. Like Domitorians, Orphanistas’ work is often inspired by a revisionist spirit, intent on uncovering the provenance, the unwritten histories, and the yet unwatched or unpreserved films. This year’s focus on radical filmmaking, radical politics on screen, and radical new practices and ideas in archiving and preservation, however, brought to the fore yet another kind of orphaned condition. The story of many of the radical films presented had in fact not only been historically neglected until recently, but was, more specifically, also a politically orphaned and muted one—one stemming from the margins of the political arena and claiming center stage, brought back to light through the loving work of preservation, scholarship, and exhibition.

This being the topic, there couldn’t have been more promising a start than the program “Movements,” spanning over six decades of radically unruly Dutch avant-garde, compiled by EYE curator Simona Monizza. This was followed by a homage to recently departed filmmaker Jonas Mekas, A Few Drunkards at the Mars Bar (2001), by Masha Godovannaya and tx-reverse, a radical interchange of representations of the temporal and spatial axes by Martin Reinhart and Virgil Widrich.

The following day opened with my keynote, examining the BFI National Archive’s preservation and recirculation of a collection of films shot in colonial India between 1899 and 1947, which I read from a postcolonial perspective. Among the titles I discussed was the early film Panorama of Calcutta from the River Ganges (1899). Accompanied on the piano by Elaine Brennan, this ghost ride is the oldest filmic record of India, depicting Varanasi’s riverfront but conveniently marketed as a picture of the better-known Calcutta in the West. By questioning notions of national film heritage and West-dominated narratives around its canonization, my keynote advocated a more radical approach to film archiving and curatorship.

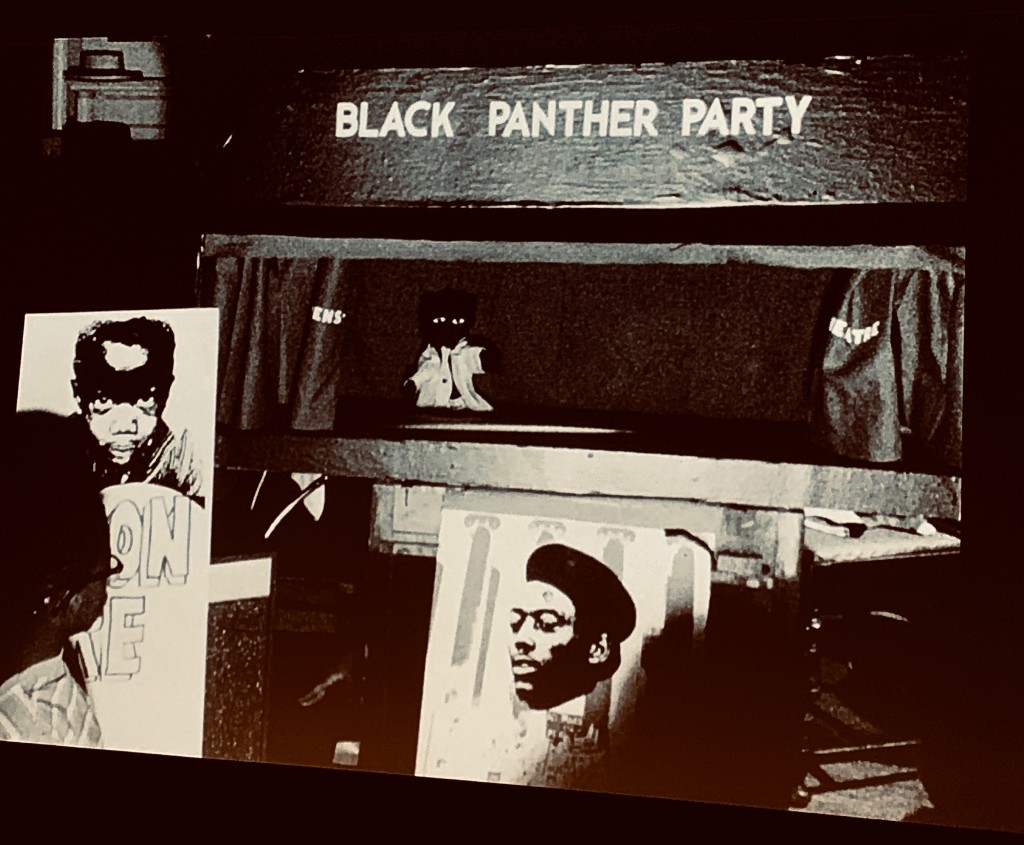

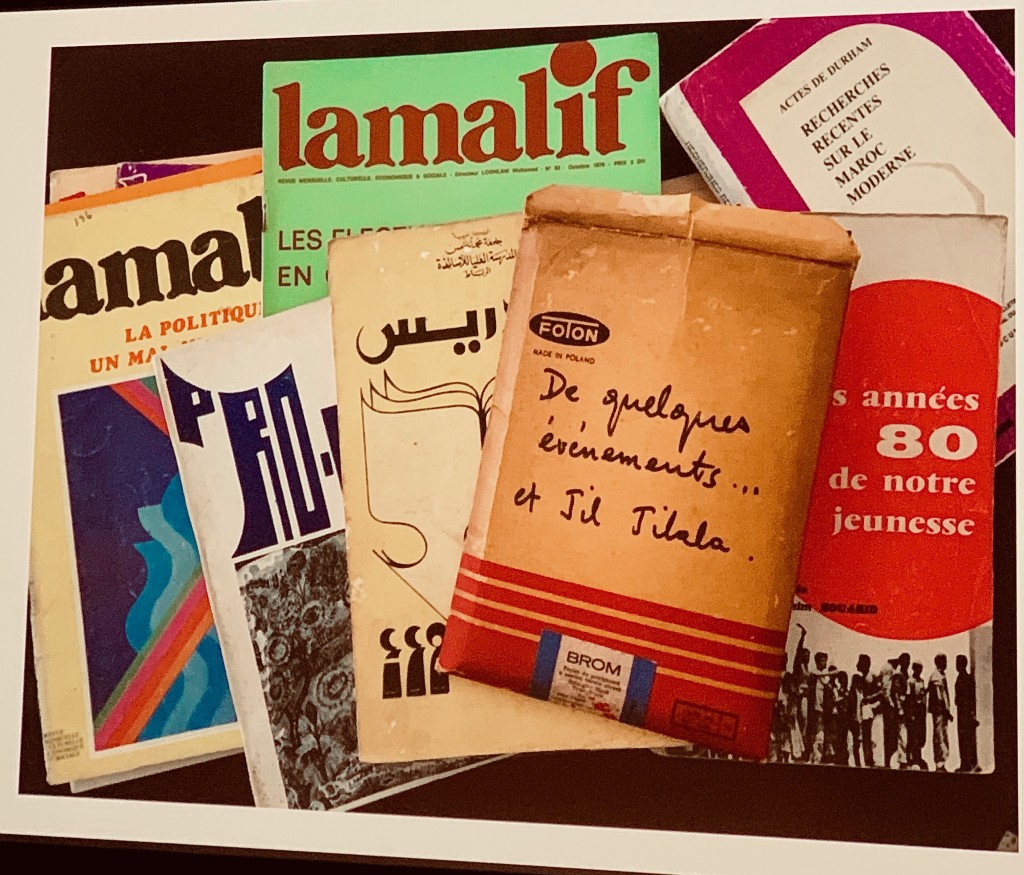

Titles such as the 16mm films Breakfast, Mayday, and Puppet Show (Pic. 2), presented by Brian Meacham (Yale Film Study Center) and filmmaker Josh Morton, for instance, offered a testimony of the Black Panther’s grassroots work in New Haven: serving free breakfast to local youth, organizing Mayday demonstrations, and performing political puppet theatre for children and grown-ups. Josh Morton shot these films in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a member of the local Black Panther chapter, before the films became part of the “Josh Morton Collection” at the Yale Film Study Centre, which preserved them in 2016. While neither Meacham nor Morton specifically addressed the history of these films’ preservation and circulation, we understand it has taken them five decades to climb to the top of the archive’s preservation priorities. They were screened in June 2017 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of their making. One might thus reasonably speculate that as the story these films depict was a radical one—an act of political radicalism conceived from the very start as a counter-narrative to mainstream media discourses criminalizing the Black Panther Party—over the decades, their preservation might have become susceptible to changing institutional priorities and political sentiments.

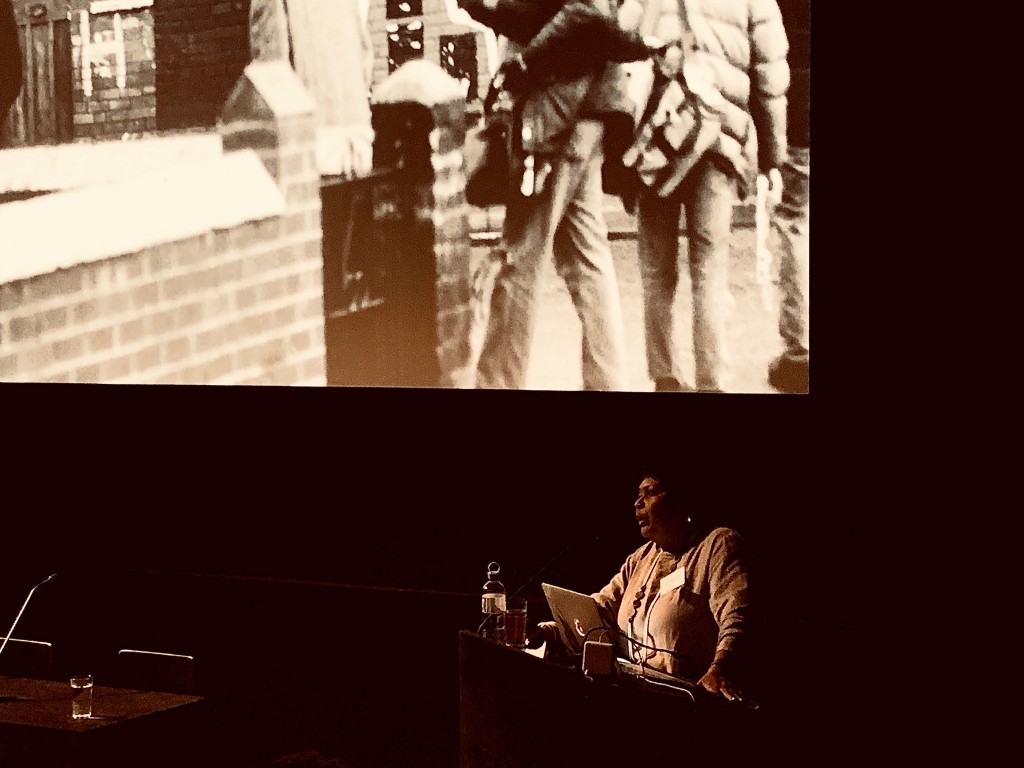

Similarly, the evening screening of St. Clair Bourne’s independent documentary The Black and the Green, presented by the deceased filmmaker’s sister Judith Bourne (Pic. 3) and Jacob Perlin (Metrograph), shed light on another radical microhistory. Rarely screened before, Bourne’s 1983 documentary chronicles a trip to Belfast by five American civil rights activists discussing the parallels and differences between the Irish and the African American liberation struggles, and the latter’s influence on many Catholics in Northern Ireland. Speaking to Sinn Féin’s member Paddy Loughran (who was killed by an off-duty policeman in 1992), Rev. Herbert Daughtry notes: “all of us who’ve been here have been very moved by the striking similarities between Irish here and Blacks: our struggles, our resilience, our humour, our kindness.” “But,” he then adds, “as you’ve pointed out, in the States, Irish and Blacks do not have a history of getting on together.” The Black and the Green is a powerful visual record of a radical internationalist collaboration and of the ensuing debate about the way in which race, ethnicity, religion, and geography intersect, determining historically specific forms of oppression and practices of resistance.

The material histories of many of the films presented at Orphans 2019 revealed transnational collaborations and cross-national journeys. This was the case of the Iran-US coproduction of Margaret Mehring and Mohammad Ali Issari’s 1977 documentary series Ancient Iran, of which Kaveh Askari (Michigan State University) and Hadi Gharabaghi (New York University) presented an episode. The archival history of Galicia, a 1936 documentary by Spanish exiled filmmaker Carlos Velo about peasant culture in the Galician region, presented by Enrique Fibla-Gutierrez (Filmoteca de Catalunya) and Pablo La Parra-Pérez (Elías Querejeta Film School), similarly spanned across multiple archives and continents. Disappeared after its screening at the 1937 Paris International Exposition during the Spanish civil war, Galicia’s recent reappearance—incorporated in the reels of Esfir Schub’s film Ispanya (Spain, 1939)—and exhibition have finally redeemed the film’s orphaned and exiled history.

The Symposium took a radically punk turn in the afternoon of day 2 with the screening of Kalkar, Hardi Volmer’s hilarious satire of Tarkovsky’s Stalker, which, as Volmer and archivist Eva Näripea (National Archives of Estonia) explained, escaped Soviet censorship and made its way to the Estonian film archive only thanks to its (delightfully) nonsensical aesthetics. This was followed by the “heroic idiocy, black humour, endless, absurd hyperactivity of . . . soldiers, sailors, doctors, and secret agents” in Evgeny Yufit’s early Necrorealist films Lesorub (Woodcutter, 1985) and Vesna (Spring, 1987). Masha Godovannaya’s (Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna) moving presentation centred on her personal investigation into Evgeny Yufit’s archive, orphaned of its creator since the artist’s death in 2016. As “an artist and filmmaker, a feminist researcher, a queer person with mixed up geographies and sense of belonging, Yufit’s artistic ally and colleague, his ex-wife and now a caretaker of his archive of film materials and artistic heritage,” Godovannaya shared with us the impossibility of finding an emotional distance and an interpretative standpoint from which to confront “the radical absence of the other” in the archive. As she explained in closing, only her positionality granted her a hermeneutic footing, an entry point into Yufit’s archive, which she begun interrogating from a post-Soviet, queer perspective.[i]

Many more filmic encounters populate my memories of Orphans 2019. What still resonates with me is the awareness that in being preserved and re-circulated, these orphaned films have not just encountered new audiences, but also been adopted by a new family, a community of caring scholars, artists, and archivists. As a transnational scholar, orphaned like many of a clear sense of affiliation, it was a pleasure to feel part of this community and take part in what I like to imagine as an Orphans International.

I’d like to thank Dan Streible, Simona Monizza, Katharina Müller, Jurij Meden, Eszter Kondor (both at the Austrian Film Museum), and Thomas C. Christensen (Danish Film Institute) for providing additional material and information about their contributions to Orphans 2019.

[i] Transcript from Céline Ruivo’s recording of Godovannaya’s presentation.